This week is the 10th anniversary of the release of the game Undertale. In 2013 I ported its Kickstarter demo (made in Game Maker 8 for Windows) to Mac OS X, and in 2015, though I was no longer needed to port the final version (due to the release of GameMaker Studio), I bug-tested the final version on Mac OS X. In addition to my bug reports, I also submitted my comprehensive initial impressions of the game to the developer.

I'm not going to be discussing or reviewing any of those impressions.

Instead, I'm simply going to write down what I think about this game, today, ten years on, as quickly as possible.

Hmm… what do I think about this game…?

I guess my take on it is… uhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh,

…wait, you have played Undertale, too, right? Maybe don't click this unless you've seen all you want to see in it for yourself.

• Well, as a metatextual narrative fan, I love how it set a not-too-contrived diegetic structure for what its metatext actually "means" – how saving and loading the game means rewinding time by sheer force of will of your soul, how the save points are points of focus for the soul's will, how that force of will is synthesised by the monsters using the DT Machine, how Flowey is able to 'save' and 'load' using his synthetic DT (inferior to your soul's), and later with the six souls, which is where all his power and knowledge comes from, and so forth. Which is to say, I like how all of the metatextual "stuff", the framing of the game verbs, as well as the horror aspects of Flowey, are connected directly to your desire to do right or wrong, and everything that happens on that level serves to test what that desire means, and what you do when it's pushed to the extreme (in multiple directions). Plenty of people dismiss this aspect as just "The Monster At The End Of This Book with extra steps" but I'll confess to being partial to this kind of emotion-outdoes-reality narrative, and I think this themed metatext gives it a consistent thematic through-line and a focused artistic goal.

• As a fan of nonlinear stories, I also like how the story of Asriel and the fallen human is first laid out at the end of the neutral route, but then subverted piece by piece as more "post-game" events unfold, and how the true character of the fallen human slowly arises, and how they are, intentionally or not, the true cause of the conflict in the game. The true "antagonist", the true source of the philosophy "In this world, it's kill or be killed", yet so far in the past that they cannot be truly challenged except by putting their legacy to rest.

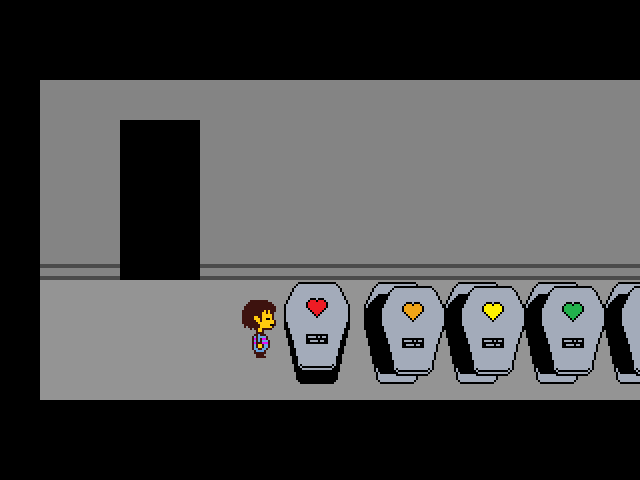

(The misdirection around the protagonist and their name - the coffin in the castle, Asgore's voice on the Game Over screen, the opening demo, which all actually refer to or depict the fallen human - is maybe a little contrived, though, in the sense that being led to believe that all of these things actually refer to your player-character doesn't exactly lead to the biggest payoff in the end, and the game is mostly imaginable without them.)

• On that note, I also feel the fallen human's general narrative role is a pretty good "ultimate revelation" for the game's backstory - every monster deeply loves the fallen human, to the point of killing six subsequent humans in their memory, but their death was actually entirely contrived as a childish mass-murder plot to break the barrier and be a hero, manipulating Asriel and inadvertently causing his death as well. Despite this phrasing of mine, it's not an overly nihilistic "it was all because of an unbelievable childish delusion" reveal, like, say, Higurashi chapter 5 (Meakashi), because the player-character is able to slowly reach the manipulated characters, undo the emotional damage, and bring peace, but it does have a similar bitter taste of tragic misunderstanding to it, and it doesn't overly hinge on convenient coincidences. In particular I think it has a lot more going on than, say, Omori's ultimate revelation (which I think is just nonsensical for its setting and characters).

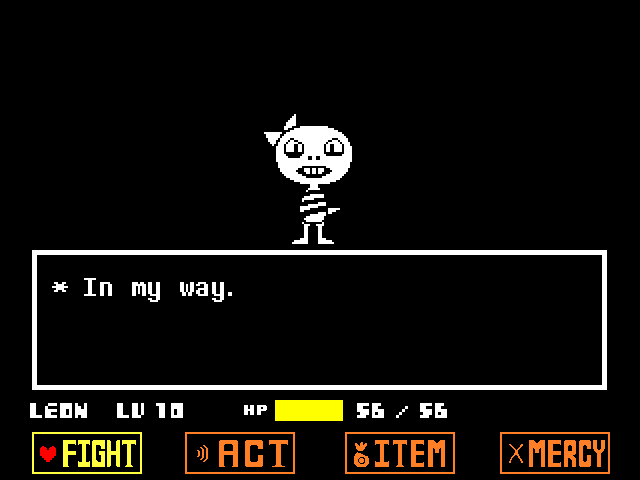

• At the time of release, and even up to today, people were obsessed with the "moral" aspect of this game, how real the moral stakes feel, how your "choices matter", and the notion that doing or not doing one route or the other says anything about you. Many people even openly deride Undertale for "guilting" the player, or inversely for "rewarding morally bad players" by giving unique content for killing Sans or whatever. For awhile I felt like this gut-reaction approach to fiction was only doing harm to Undertale's reputation, but now I guess I feel like the game serves as a gentle challenge to the reader to overcome these assumptions.

I think the assumption that "being guilted by a game is bad" has arisen from bad attempts at guilting the player in other games, before and since. In reality, being guilted by a game is OK. Not in the sense that "the game is right and the player should never do morally bad acts", but in the sense that it's OK to do morally bad acts in a game to experience guilt. Games are a kind of fiction - a kind of entertainment - that let you experience a lot of unique things, and it's OK if guilt, remorse, and other such emotions, are among them - and even if these emotions are alongside more entertaining emotions like "pride at defeating a boss" or "surprise at a character's reaction to adversity". What really matters is how entertaining it feels, which comes down to whether the emotion feels realistic or not. Other games with "moral consequences" often fail at making being judged feel meaningful because they fail to properly sell the meaning of the guilt. By making the moral stakes feel real (or at least as real as possible within the game's authorial voice), I think Undertale works as a potential example to show how a game can artfully convey guilt without pretending to be higher or more rarefied than entertainment.

• In terms of narrative execution, I'd say the biggest Homestuck influence is how it carefully doles out information to the first-time player, so as to presuppose a conclusion just before its antithesis is revealed. A huge example is the slow reveal of Asgore: in the ruins, sparse lines of dialogue simply cast Asgore as a malevolent being that wants you dead; in Snowdin the king Dreemur is presented as a jolly, beloved fellow; Undyne reveals that Dreemur's first name is Asgore. Then you meet him and the Asriel backstory shows how these disparate concepts are all united. Homestuck did this kind of thing quite a bit (compare the slow reveal of Calliope and, indirectly, Caliborn) and I think it works wonders for overall pacing and emphasising somewhat nuanced character motivations for even not-particularly-attentive players and streamers.

• On a design angle, I think Undertale's done a decent service to games by serving as a popular contemporary example of how to make funny or intense things happen to the player in an ostensibly "unconstrained" game situation, without having to resort to the firm authorial grip of cutscenes, by instead just cheating or fudging things, and trusting the player not to notice or care. The Flowey boss fight and its non-linear player health bar, or the unfair tile maze in Hotland, or the "Toriel crit" (or even incredibly subtle stuff like changing item messages during "serious" bosses) are all engineered to make it look like something is organically happening, and it all by-and-large works out. A lot of this isn't too different from things like the Clumsy Robot fight in EarthBound (among other fights in that game) but there's a lot more varied and obvious examples in this game.

• To conclude, I think the other positive example Undertale has set for this past decade's games is that of showing how funny, beautiful, or even highly important scenes (as in, Shyren's concert, the Lesser Dog sculptures, and most of the worst route) can just be missable or obscure within even an ostensibly very linear game. I know this has given the game infamy as a "backseating" game among streamers (in terms of chatters trying to force certain funny missables to be seen), but for people who are willing to let surprises come to them, it does give this game an intimate feeling when you realise you caused something strange and rare to happen. I, for one, love that sort of thing dearly. I partly suspect the reason the game was designed like this is due to assumptions by Toby Fox about how small it is playthrough-wise (which, well, it both is and isn't), and wanting to make multiple playthroughs feel more satisfying, but I think games of all sizes (including Deltarune) benefit from it. Certainly, I think Void Stranger (to name one example) would hardly have been the game it is without Undertale far in the background.